My name is Michael Lambrix and for 30 years now I have been condemned to death in the State of Florida. I am but one of the many though who have been not simply sentenced to death by the hands of a corrupt judicial system, but condemned to a fate even worse than death – condemned to over a quarter of a century of continuously “living” and slowly dying in solitary confinement as the world outside slips further and further away each day.

It would be only too easy to act with indifference to my claim that I have been wrongfully convicted and condemned to death – that I am innocent of the crime that had sent me here. But can any of us any longer deny the fact that too many have been already proven innocent and released after spending sometimes many decades on death row for a crime they were innocent of? And with so many already proven innocent and released, doesn’t it stand to reason that there are many more still suffering the ultimate injustice – convicted and condemned to death in spite of innocence?

Recently my entire case has been put on the internet for all to see. including the trial transcripts. Not just what I claim happened, but both sides. As far as I know, this has never been done before. So, for the first time ever, anyone in the world with access to internet can now look at the entire case themselves – the entire actual trial transcripts, the entire appeals briefs and court decisions, everything. I hope that all of you will take a look.

This case – the case of State of Florida v. Michael Lambrix – has been selected to be profiled, as this capital case raises a substantial and supported claim of innocence that questions just how such a capital case is prosecuted. In a circumstantial case, the question if innocence is seldom clear cut. The evidence must be diligently reviewed and the determination of guilt or innocence must be weighed carefully.

A full summary of this capital case is now provided below. The facts presented are taken from the actual trial transcript and court records as well as publications such as published newspaper accounts of the case. Both sides of this capital case are now provided so that you can independently review the actual trial transcript and post conviction appellate proceedings in their entirety, then you can determine for yourself whether justice has been served.

As you fully review the case; and fully read the court records, ask yourself whether, given the manner in which our courts have reviewed this case and resolved the issue of innocence raised, does the evidence support the verdict originally rendered by the jury, or did the state deliberately convict and condemn an innocent man? Is our judicial system capable of, and willing to, protect the innocent from being executed by providing a full and fair review of a legitimate claim of innocence raised in a capital case?

IV. Just what is “Capital Murder?”

Before we proceed to the summary of the capital case profiled, we must take a moment to understand the concept of “capital murder.” By law the death penalty can only be imposed upon the “worst of the worst” of those convicted of murder. As the Supreme Court recognized in Edmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982), the death penalty can only be imposed upon those who intended to commit a crime that resulted in death.

Laws are established to distinguish the varying “degrees” of murder. A prosecutor is required to prove beyond a reasonable doubt the elements necessary to establish the degree of murder charged before a jury can convict, reflecting “a fundamental value determination of our society that it is far worse to convict an innocent man than to let a guilty man go free.” In Re Winship, 397 U.S. 358, at 372 (1970).

Generally there are two types of capital “first degree” murder upon which a death sentence can be imposed. If a person is found guilty of committing a murder with premeditated intent, such as contract killing, or alternately commits a felony (such as robbery) in which a person is killed “during the commission of the crime” they can be found guilty of capital first degree murder and possibly face a sentence of death.

If the jury determines that the defendant did kill the alleged victim, but the evidence does not prove the intent necessary for a conviction of first degree murder, then the jury can convict him or a lesser degree of murder.

Second degree murder is characterized by the absence of formed intent, but still exhibits a malicious indifference to the taking of a life that resulted in the death. Third degree (or manslaughter) is generally defined as criminally negligent conduct resulting in the unintentional death of another. Last, the law recognizes the concept of “justifiable homicide” when the death of another is the result if a legally justified circumstance, such as self defense.

By establishing these laws that define the elements of proof necessary to convict in each “degree” of murder, our legal system protects the accused from being subjected to disproportionate punishment. For example, a person can maliciously kill another without forming the prerequisite element of intent necessary to convict of capital murder in a spontaneous event or “heat of passion,” such as the escalation of a fight, and be convicted of only second degree murder.

Equally so, if someone attempts to physically attack you, and you believe you are in imminent danger of serious bodily harm or even death, the law allows you to take the action necessary to defend yourself – including the use of deadly force when no other reasonable alternative exists at the moment.

Before a case is ever brought before a jury, a prosecutor must examine the evidence and determine the degree of murder to be charged. Contrary to popular myth, a prosecutor does not represent the victim, but is ethically obligated to seek justice and must protect the rights of the accused as well as the victim. A prosecutor is an “officer of the court” and is obligated to ensure that justice is served, which includes ensuring that the accused receives a fair trial.

In Berber v. United States, 295 U.S. 78 (12935) the Supreme Court recognized that a prosecutor cannot engage in improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction” without violating his oath of office – and violating the fundamental constitutional rights of the accused, thereby invalidating any conviction obtained by such prosecutorial misconduct.

Unfortunately, too often ambitious prosecutors will cross the line and seek to win a conviction by any means necessary. Overzealous prosecution has become a common form of prosecutorial misconduct in capital cases despite the appellate courts’ repeated admonishments. See, Gore v. State, 719 So. 2d 1197 (Fla. 1999) (vacating capital conviction because of overzealous prosecutorial misconduct); Ruiz v. State, 743 So. 2d 1 (Fla.1999) (recognizing the continuing problem of overzealous “win by any means necessary” prosecutorial misconduct in Florida capital cases).

A second level of safeguard to protect against an overzealous prosecution resulting in a conviction disproportionate to the actual crime is the jury system itself, as ultimately the jury must decide the degree of murder the evidence actually supports – or whether the evidence supports beyond a reasonable doubt any verdict of guilt at all.

However, this jury system can be, and all too often is, deliberately manipulated by ethically corrupt prosecutors more interested in promoting their personal careers by winning a big conviction than fulfilling their ethical obligations to serve justice. The fact is that unethical, overzealous prosecution is on of the leading causes of wrongful convictions in capital cases.

Charles Dickens once wrote that there is nothing more profoundly perceived – and more profoundly felt – as an injustice. At some point of our lives most of us have personally experienced the malicious sting of an unfounded accusation… accused of something that we knew we did not do, and we knew was not true!

As fully summarized below – and as the actual court records reflect – in this case, there were no eyewitnesses, no physical or forensic evidence, and no confessions to support the state’s theory of premeditated capital murder. The prosecutor readily conceded that the entire case brought against Michael Lambrix was built upon the testimony of a single key witness, Frances Smith (now Frances Ottinger) who at the time was Lambrix’s estranged ex girlfriend – and who only came forward with her story that Lambrix told her he intended to commit murder after she was arrested herself on unrelated felony charges… which were conveniently dropped shortly after she became a state witness.

This case, however, is more about what the jury was not allowed to hear – what the state attorney’s office deliberately kept from the jury that if revealed would have made all the difference. Incredibly, the prosecutor in this case (Randall McGruther) has a history of alleged prosecutorial misconduct, and has sent at least one other innocent man to death row. Please read, “The Anatomy of a Corrupt Prosecutor.”

Notably, the jury was not allowed to hear that in fact, key witness Smith had actually told numerous conflicting stories to law enforcement officials before coming up with the one the prosecutor used at trial – and she had also failed a polygraph (lie detector) test the state gave her before trial. Nor was the jury allowed to hear that the male “victim” in this capital case was a known career criminal with a history of violently assaulting women.

More significantly, as the record reflects, when Lambrix advised the trial court that he wanted to testify at trial in his own defense against his lawyer’s wishes, the trial court illegally prohibited Lambrix from doing so; see, Lambrix v. Singletary, 72 F. 3d 1500 (11th Cir. 1996) and virtually no defense was presented. In subsequent appellate proceedings, the evidence would later establish that the state knew along that Lambrix claimed to have acted in involuntary self defense when attempting to stop the male victim from fatally assaulting the young woman, and that the state’s own evidence supported Lambrix’s claims… this leads one to wonder if perhaps the prosecutor unethically used his influence to deliberately prevent the jury from hearing any of the evidence that would have established self defense.

Many years later, long after Lambrix had lost his state and federal appeals, and even came within hours of execution, a substantial wealth of evidence was exposed that arguably revealed one of the most extreme cases of prosecutorial misconduct imaginable.

By early 1998 Lambrix had already been on Florida’s “death row” almost 14 years and had just lost an appeal before the Supreme Court by a marginal 5 to 4 vote; Lambrix v. Singletary, 520 U.S. 518 (1997) and was prepared to be sent back to “death watch” to face imminent execution when Deborah Hanzel, a former state witness, came forth and admitted that she had lied at Lambrix’s trial.

At the time Lambrix stood trial, Hanzel was the girlfriend of key witness Smith’s cousin, and had testified that Lambrix also told her he committed the crime – Hanzel was the only witness who corroborated key witness Smith’s otherwise unsupported testimony of an actual intent to kill.

Now, Hanzel said she had lied – that Lambrix never actually told her he killed anyone. Hanzel provided the court with an affidavit detailing how they knew all along that Lambrix had acted in self defense “when the guy went nuts,” but that key witness Smith and the states attorney’s lead investigator had coerced her to fabricate a story to corroborate Frances Smith’s testimony – and to make sure the jury did not hear any evidence that Lambrix acted in self defense. See, the Affidavit of Deborah Hanzel.

An investigation was conducted and telephonic records from 1983 substantiated Hanzel’s claims. During the course of this investigation even more startling information was revealed when key witness Smith’s recently divorced ex-husband, Doug, informed Lambrix’s legal counsel that during the time Lambrix was being prosecuted, key witness Smith was having an affair “of a sexual nature” with the local state attorney’s lead investigator on the case, Robert Daniels.

In a subsequent hearing in April 2004 key witness Frances Smith was compelled to again testify – and with great reluctance, Smith admitted that she did have a sexual affair with Robert Daniels, the state’s lead investigator and that they deliberately concealed this information. See,”Wittness admits to affair with investigator,” Ft. Myers News-Press (Apr. 6, 2004)

Robert Daniels was a crucial member if the prosecution team. Court records show that it was Daniels who actually swore out the affidavit leading to formal charges of capital murder being brought against Lambrix, subsequently, Daniels then personally supervised the development of the wholly circumstantial evidence used to convict and condemn Lambrix, including crucial evidence that has now been shown to have been deliberately fabricated with the intent of wrongfully convicting Lambrix – and that the prosecutor knew that this crucial testimony and evidence was fabricated.

In a case such as this, where a first jury trial ended in a “hung jury” because the first jury was unable to reach any verdict of guilt, what if the jury that did convict and condemn Lambrix had known of this deliberately concealed evidence? What if the jury had heard all the evidence not only of Lambrix’s claim of self defense, but evidence establishing the motive the witnesses and the motive the state attorney’s office had in deliberately fabricating this case of capital murder brought against Lambrix? Would this now exposed evidence have made any difference?

As you read the case summary fully provided below and review for yourself the actual trial transcript and presently pending appeal briefs, try to imagine yourself as an actual juror in this capital case. Carefully consider all the evidence, both presented at trial, as well as the evidence now revealed through the post conviction appellate proceedings. Then you decide – did a corrupt prosecutor, by deliberate intent and design, wrongfully convict and condemn an innocent man? Was it capital murder – or was it self defense? The evidence is now in your hands, and you have the opportunity to decide the fate of this condemned man. Carefully consider both sides; then you decide… you be the jury.

V.) Summary of State of Florida v. Michael Lambrix

The capital case brought against Michael Lambrix began in February 1983, as the rural farming community of LaBelle, Florida prepared to celebrate its annual “Swamp Cabbage Festival.” The top story around the small southern town was that a 19 year old waitress had been reported missing. Aleisha Bryant, the youngest daughter of a well known local family, was last seen with an older man known only as “Chip” that past Saturday night at a rowdy bar just across the county line called “Squeaky’s.”

A full summary of this capital case is now provided below. The facts presented are taken from the actual trial transcript and court records as well as publications such as published newspaper accounts of the case. Both sides of this capital case are now provided so that you can independently review the actual trial transcript and post conviction appellate proceedings in their entirety, then you can determine for yourself whether justice has been served.

As you fully review the case; and fully read the court records, ask yourself whether, given the manner in which our courts have reviewed this case and resolved the issue of innocence raised, does the evidence support the verdict originally rendered by the jury, or did the state deliberately convict and condemn an innocent man? Is our judicial system capable of, and willing to, protect the innocent from being executed by providing a full and fair review of a legitimate claim of innocence raised in a capital case?

IV. Just what is “Capital Murder?”

Before we proceed to the summary of the capital case profiled, we must take a moment to understand the concept of “capital murder.” By law the death penalty can only be imposed upon the “worst of the worst” of those convicted of murder. As the Supreme Court recognized in Edmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982), the death penalty can only be imposed upon those who intended to commit a crime that resulted in death.

Laws are established to distinguish the varying “degrees” of murder. A prosecutor is required to prove beyond a reasonable doubt the elements necessary to establish the degree of murder charged before a jury can convict, reflecting “a fundamental value determination of our society that it is far worse to convict an innocent man than to let a guilty man go free.” In Re Winship, 397 U.S. 358, at 372 (1970).

Generally there are two types of capital “first degree” murder upon which a death sentence can be imposed. If a person is found guilty of committing a murder with premeditated intent, such as contract killing, or alternately commits a felony (such as robbery) in which a person is killed “during the commission of the crime” they can be found guilty of capital first degree murder and possibly face a sentence of death.

If the jury determines that the defendant did kill the alleged victim, but the evidence does not prove the intent necessary for a conviction of first degree murder, then the jury can convict him or a lesser degree of murder.

Second degree murder is characterized by the absence of formed intent, but still exhibits a malicious indifference to the taking of a life that resulted in the death. Third degree (or manslaughter) is generally defined as criminally negligent conduct resulting in the unintentional death of another. Last, the law recognizes the concept of “justifiable homicide” when the death of another is the result if a legally justified circumstance, such as self defense.

By establishing these laws that define the elements of proof necessary to convict in each “degree” of murder, our legal system protects the accused from being subjected to disproportionate punishment. For example, a person can maliciously kill another without forming the prerequisite element of intent necessary to convict of capital murder in a spontaneous event or “heat of passion,” such as the escalation of a fight, and be convicted of only second degree murder.

Equally so, if someone attempts to physically attack you, and you believe you are in imminent danger of serious bodily harm or even death, the law allows you to take the action necessary to defend yourself – including the use of deadly force when no other reasonable alternative exists at the moment.

Before a case is ever brought before a jury, a prosecutor must examine the evidence and determine the degree of murder to be charged. Contrary to popular myth, a prosecutor does not represent the victim, but is ethically obligated to seek justice and must protect the rights of the accused as well as the victim. A prosecutor is an “officer of the court” and is obligated to ensure that justice is served, which includes ensuring that the accused receives a fair trial.

In Berber v. United States, 295 U.S. 78 (12935) the Supreme Court recognized that a prosecutor cannot engage in improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction” without violating his oath of office – and violating the fundamental constitutional rights of the accused, thereby invalidating any conviction obtained by such prosecutorial misconduct.

Unfortunately, too often ambitious prosecutors will cross the line and seek to win a conviction by any means necessary. Overzealous prosecution has become a common form of prosecutorial misconduct in capital cases despite the appellate courts’ repeated admonishments. See, Gore v. State, 719 So. 2d 1197 (Fla. 1999) (vacating capital conviction because of overzealous prosecutorial misconduct); Ruiz v. State, 743 So. 2d 1 (Fla.1999) (recognizing the continuing problem of overzealous “win by any means necessary” prosecutorial misconduct in Florida capital cases).

A second level of safeguard to protect against an overzealous prosecution resulting in a conviction disproportionate to the actual crime is the jury system itself, as ultimately the jury must decide the degree of murder the evidence actually supports – or whether the evidence supports beyond a reasonable doubt any verdict of guilt at all.

However, this jury system can be, and all too often is, deliberately manipulated by ethically corrupt prosecutors more interested in promoting their personal careers by winning a big conviction than fulfilling their ethical obligations to serve justice. The fact is that unethical, overzealous prosecution is on of the leading causes of wrongful convictions in capital cases.

Charles Dickens once wrote that there is nothing more profoundly perceived – and more profoundly felt – as an injustice. At some point of our lives most of us have personally experienced the malicious sting of an unfounded accusation… accused of something that we knew we did not do, and we knew was not true!

As fully summarized below – and as the actual court records reflect – in this case, there were no eyewitnesses, no physical or forensic evidence, and no confessions to support the state’s theory of premeditated capital murder. The prosecutor readily conceded that the entire case brought against Michael Lambrix was built upon the testimony of a single key witness, Frances Smith (now Frances Ottinger) who at the time was Lambrix’s estranged ex girlfriend – and who only came forward with her story that Lambrix told her he intended to commit murder after she was arrested herself on unrelated felony charges… which were conveniently dropped shortly after she became a state witness.

This case, however, is more about what the jury was not allowed to hear – what the state attorney’s office deliberately kept from the jury that if revealed would have made all the difference. Incredibly, the prosecutor in this case (Randall McGruther) has a history of alleged prosecutorial misconduct, and has sent at least one other innocent man to death row. Please read, “The Anatomy of a Corrupt Prosecutor.”

Notably, the jury was not allowed to hear that in fact, key witness Smith had actually told numerous conflicting stories to law enforcement officials before coming up with the one the prosecutor used at trial – and she had also failed a polygraph (lie detector) test the state gave her before trial. Nor was the jury allowed to hear that the male “victim” in this capital case was a known career criminal with a history of violently assaulting women.

More significantly, as the record reflects, when Lambrix advised the trial court that he wanted to testify at trial in his own defense against his lawyer’s wishes, the trial court illegally prohibited Lambrix from doing so; see, Lambrix v. Singletary, 72 F. 3d 1500 (11th Cir. 1996) and virtually no defense was presented. In subsequent appellate proceedings, the evidence would later establish that the state knew along that Lambrix claimed to have acted in involuntary self defense when attempting to stop the male victim from fatally assaulting the young woman, and that the state’s own evidence supported Lambrix’s claims… this leads one to wonder if perhaps the prosecutor unethically used his influence to deliberately prevent the jury from hearing any of the evidence that would have established self defense.

Many years later, long after Lambrix had lost his state and federal appeals, and even came within hours of execution, a substantial wealth of evidence was exposed that arguably revealed one of the most extreme cases of prosecutorial misconduct imaginable.

By early 1998 Lambrix had already been on Florida’s “death row” almost 14 years and had just lost an appeal before the Supreme Court by a marginal 5 to 4 vote; Lambrix v. Singletary, 520 U.S. 518 (1997) and was prepared to be sent back to “death watch” to face imminent execution when Deborah Hanzel, a former state witness, came forth and admitted that she had lied at Lambrix’s trial.

At the time Lambrix stood trial, Hanzel was the girlfriend of key witness Smith’s cousin, and had testified that Lambrix also told her he committed the crime – Hanzel was the only witness who corroborated key witness Smith’s otherwise unsupported testimony of an actual intent to kill.

Now, Hanzel said she had lied – that Lambrix never actually told her he killed anyone. Hanzel provided the court with an affidavit detailing how they knew all along that Lambrix had acted in self defense “when the guy went nuts,” but that key witness Smith and the states attorney’s lead investigator had coerced her to fabricate a story to corroborate Frances Smith’s testimony – and to make sure the jury did not hear any evidence that Lambrix acted in self defense. See, the Affidavit of Deborah Hanzel.

An investigation was conducted and telephonic records from 1983 substantiated Hanzel’s claims. During the course of this investigation even more startling information was revealed when key witness Smith’s recently divorced ex-husband, Doug, informed Lambrix’s legal counsel that during the time Lambrix was being prosecuted, key witness Smith was having an affair “of a sexual nature” with the local state attorney’s lead investigator on the case, Robert Daniels.

In a subsequent hearing in April 2004 key witness Frances Smith was compelled to again testify – and with great reluctance, Smith admitted that she did have a sexual affair with Robert Daniels, the state’s lead investigator and that they deliberately concealed this information. See,”Wittness admits to affair with investigator,” Ft. Myers News-Press (Apr. 6, 2004)

Robert Daniels was a crucial member if the prosecution team. Court records show that it was Daniels who actually swore out the affidavit leading to formal charges of capital murder being brought against Lambrix, subsequently, Daniels then personally supervised the development of the wholly circumstantial evidence used to convict and condemn Lambrix, including crucial evidence that has now been shown to have been deliberately fabricated with the intent of wrongfully convicting Lambrix – and that the prosecutor knew that this crucial testimony and evidence was fabricated.

In a case such as this, where a first jury trial ended in a “hung jury” because the first jury was unable to reach any verdict of guilt, what if the jury that did convict and condemn Lambrix had known of this deliberately concealed evidence? What if the jury had heard all the evidence not only of Lambrix’s claim of self defense, but evidence establishing the motive the witnesses and the motive the state attorney’s office had in deliberately fabricating this case of capital murder brought against Lambrix? Would this now exposed evidence have made any difference?

As you read the case summary fully provided below and review for yourself the actual trial transcript and presently pending appeal briefs, try to imagine yourself as an actual juror in this capital case. Carefully consider all the evidence, both presented at trial, as well as the evidence now revealed through the post conviction appellate proceedings. Then you decide – did a corrupt prosecutor, by deliberate intent and design, wrongfully convict and condemn an innocent man? Was it capital murder – or was it self defense? The evidence is now in your hands, and you have the opportunity to decide the fate of this condemned man. Carefully consider both sides; then you decide… you be the jury.

V.) Summary of State of Florida v. Michael Lambrix

The capital case brought against Michael Lambrix began in February 1983, as the rural farming community of LaBelle, Florida prepared to celebrate its annual “Swamp Cabbage Festival.” The top story around the small southern town was that a 19 year old waitress had been reported missing. Aleisha Bryant, the youngest daughter of a well known local family, was last seen with an older man known only as “Chip” that past Saturday night at a rowdy bar just across the county line called “Squeaky’s.”

- Building where Squeaky's Bar was located - photo taken in 2014 -

Initially, the investigation revealed that “Chip” had only recently come to town under the false identity of Lawrence Lamberson, but was in fact actually Clarence Edward Moore, a 35 year old ex-con and career criminal with a history of violence against women and a known associate of South Florida drug smugglers; Moore could not be located either.

A few days later Moore’s car was located up near Tampa being driven by Frances Smith, who was arrested on unrelated felony charges. When asked about the car, Smith told police that it belonged to her boyfriend – but she couldn’t remember his name. After Smith was arrested, the car was impounded. Smith remained in custody for several days and gave various law enforcement personnel numerous conflicting stories before being bonded out by her family. The following week Smith, now accompanied by her own lawyer, went to the state attorney’s office in Tampa to “voluntarily” report a double homicide.

Smith told how a few months earlier just after Christmas she had abruptly abandoned her three young children and 14 years of marriage to run away with the much younger “Mike” Lambrix. Traveling together to LaBelle, they took up residence in a rented trailer on a ranch in nearby Glades County. There they lived under the assumed name “Townsend,” as Lambrix had recently walked away from a minimum security state work release center where he was serving a sentence for passing a worthless check – Lambrix’s only prior criminal conviction.

Initially, the investigation revealed that “Chip” had only recently come to town under the false identity of Lawrence Lamberson, but was in fact actually Clarence Edward Moore, a 35 year old ex-con and career criminal with a history of violence against women and a known associate of South Florida drug smugglers; Moore could not be located either.

A few days later Moore’s car was located up near Tampa being driven by Frances Smith, who was arrested on unrelated felony charges. When asked about the car, Smith told police that it belonged to her boyfriend – but she couldn’t remember his name. After Smith was arrested, the car was impounded. Smith remained in custody for several days and gave various law enforcement personnel numerous conflicting stories before being bonded out by her family. The following week Smith, now accompanied by her own lawyer, went to the state attorney’s office in Tampa to “voluntarily” report a double homicide.

Smith told how a few months earlier just after Christmas she had abruptly abandoned her three young children and 14 years of marriage to run away with the much younger “Mike” Lambrix. Traveling together to LaBelle, they took up residence in a rented trailer on a ranch in nearby Glades County. There they lived under the assumed name “Townsend,” as Lambrix had recently walked away from a minimum security state work release center where he was serving a sentence for passing a worthless check – Lambrix’s only prior criminal conviction.

- The trailer Lambrix and Frances rented, photo taken many years later -

On the evening of Saturday February 5th Lambrix and Smith went to the “Town Tavern” in LaBelle, where they then met Moore and Bryant. The four traveled together to Squeaky’s, where they drank and danced until the bar closed. They all agreed to go back to Lambrix’s place for a late night dinner as Bryant had to be back at work at “White’s Restaurant” in just a few hours, and Moore had already checked out of his motel room and was leaving town.

Smith claimed that after arriving at the trailer she began cooking a spaghetti dinner as Lambrix, Moore, and Bryant sat in the adjacent living room. Smith later testified that they were all “laughing, teasing, and playing around” when Lambrix and Moore decided to go outside. About 20 minutes later Lambrix returned alone looking “normal,” and told Smith and Bryant that Moore wanted to show them something outside. Smith stayed behind as she continued cooking. About 45 minutes later Lambrix again returned alone – but this time was “covered in blood,” and told Smith that “they’re dead.”

According to Smith, she then followed Lambrix to the bathroom and as he washed up, she asked him what happened. Smith claimed that Lambrix refused to talk about it. Together, Lambrix and Smith went to a nearby store to purchase a flashlight and shovel. After returning to the trailer, Smith claims that Lambrix then “forced” her to assist in superficially concealing the two bodies, then fleeing the area together in Moore’s car.

Smith was given a polygraph (lie detector) test by the state attorney’s office, which showed “significant sign’s of deception,” yet based exclusively upon Smith’s specious account a warrant charging Lambrix with capital “premeditated” murder was issued and a statewide “manhunt” ensued. Several weeks later Lambrix was arrested in Orlando, Florida.

Lambrix was immediately transferred to the small, two-cell Glades County jail in Moore haven, Florida. Almost immediately the local state attorney Randall McGruther attempted to illegally have Lambrix questioned. A local inexperienced public defender was assigned to represent Lambrix, but was abruptly removed after allegations that he provided the state attorney with “confidential” information. Another public defender with even less experience was then assigned. Motions were filed to have the case transferred to another county because of graphically sensationalized stories in the local weekly newspaper, but they were summarily denied. By December 1983 the case was brought to trial at the small courthouse in Moore Haven with Judge Adams presiding.

From the time of his arrest, Lambrix steadfastly maintained his innocence, and pled “not guilty” – insisting that Smith was lying. Lambrix’s attorney advised him that the state would reduce the charges to “second degree murder” if Lambrix would plead guilty, but Lambrix refused. The trial would now commence.

On the evening of Saturday February 5th Lambrix and Smith went to the “Town Tavern” in LaBelle, where they then met Moore and Bryant. The four traveled together to Squeaky’s, where they drank and danced until the bar closed. They all agreed to go back to Lambrix’s place for a late night dinner as Bryant had to be back at work at “White’s Restaurant” in just a few hours, and Moore had already checked out of his motel room and was leaving town.

Smith claimed that after arriving at the trailer she began cooking a spaghetti dinner as Lambrix, Moore, and Bryant sat in the adjacent living room. Smith later testified that they were all “laughing, teasing, and playing around” when Lambrix and Moore decided to go outside. About 20 minutes later Lambrix returned alone looking “normal,” and told Smith and Bryant that Moore wanted to show them something outside. Smith stayed behind as she continued cooking. About 45 minutes later Lambrix again returned alone – but this time was “covered in blood,” and told Smith that “they’re dead.”

According to Smith, she then followed Lambrix to the bathroom and as he washed up, she asked him what happened. Smith claimed that Lambrix refused to talk about it. Together, Lambrix and Smith went to a nearby store to purchase a flashlight and shovel. After returning to the trailer, Smith claims that Lambrix then “forced” her to assist in superficially concealing the two bodies, then fleeing the area together in Moore’s car.

Smith was given a polygraph (lie detector) test by the state attorney’s office, which showed “significant sign’s of deception,” yet based exclusively upon Smith’s specious account a warrant charging Lambrix with capital “premeditated” murder was issued and a statewide “manhunt” ensued. Several weeks later Lambrix was arrested in Orlando, Florida.

Lambrix was immediately transferred to the small, two-cell Glades County jail in Moore haven, Florida. Almost immediately the local state attorney Randall McGruther attempted to illegally have Lambrix questioned. A local inexperienced public defender was assigned to represent Lambrix, but was abruptly removed after allegations that he provided the state attorney with “confidential” information. Another public defender with even less experience was then assigned. Motions were filed to have the case transferred to another county because of graphically sensationalized stories in the local weekly newspaper, but they were summarily denied. By December 1983 the case was brought to trial at the small courthouse in Moore Haven with Judge Adams presiding.

From the time of his arrest, Lambrix steadfastly maintained his innocence, and pled “not guilty” – insisting that Smith was lying. Lambrix’s attorney advised him that the state would reduce the charges to “second degree murder” if Lambrix would plead guilty, but Lambrix refused. The trial would now commence.

- Randall McGruther -

VI.) Taking the Case to a Jury Trial

After several days of jury selection, the actual trial began. In his opening arguments the prosecutor Randall McGruther conceded that there were no eyewitnesses, no physical or forensic evidence, and no confessions to support his theory if alleged premeditated murder – that the entire case was built up upon Frances Smith’s testimony, supported only by a web of circumstantial evidence that collectively “proved” premeditated murder.

Smith was called as the states star witness. She testified that by chance they met Moore and Bryant at the bar that night and “partied” together until the early morning hours. Lambrix then invited them back to the trailer. After an hour or so of “laughing, teasing, and playing around” Lambrix and Moore went outside only to have Lambrix return 20 alone minutes later. Lambrix then took Bryant out was gone for about 45 minutes before again returning alone – only this time Lambrix was “covered in blood” and told her “they’re dead.”

Smith then testified that while covered in blood, Lambrix grabbed her and threatened her – but incredibly did not get any blood on her or her clothing. Smith then claimed that Lambrix told her that he had hit the man in the back of the head, then choked Bryant before placing her face down in a pond to ensure that she died, even though medical evidence objectively showed that Moore was not hit in the back of the head, and there was no evidence that Bryant was choked or strangled – and no “pond” existed anywhere in that pasture area.

Smith implied that the motive was to steal Moore’s car – the very car that she alone was found in possession of. This otherwise unsupported theory of alleged premeditated murder was corroborated by state witness Deborah Hanzel, who at the time was the girlfriend of Smith’s cousin.

Hanzel testified that Lambrix also told her that he had killed Moore and Bryant so he could steal the car – but years later Hanzel recanted that testimony, claiming that Smith and the state had coerced her to provide false testimony and that Lambrix never told her he killed anyone. See, “Witness recants testimony in murder case,” Ft. Myers News-Press (Feb. 10, 2004)

Additional witnesses were called to establish particulars regarding the alleged crime scene and recovery if the two bodies. The local medical examiner, Dr. Robert Shultz, testified as to the cause of death of both Moore and Bryant. Dr. Shultz said that there was no question that Moore died of blunt force trauma resulting from numerous blows to the frontal temple area on both sides of his head, as if the blows were administered in a “swinging” fashion while Moore presumably faced his assailant. There were no blows to the back of the head (as Smith claimed), and no defense wounds – suggesting that Moore may have been the aggressor.

Robert “Bob” Daniels testified that he was the lead investigator assigned to the case, and was responsible for initiating the changes against Lambrix, then personally supervising the development of the wholly circumstantial case. Carla Mitar testified that she too was assigned by the state attorney’s office to assist in the investigation and development of the evidence. But the jury would not know that during the time Investigator Daniels, although married to Joan Daniels, was having an affair with Carla Mitar (who he later would marry). Many years later it would also be revealed that in addition to having an illicit affair with Carla Mitar, Daniels was also having a secret relationship “of a sexual nature” with star witness Frances Smith. See, “Witness admits affair with investigator,” Ft. Myers News-Press (Apr. 6, 2004).

Lambrix legal counsel were prohibited from revealing to the jury that star witness Frances Smith had told numerous conflicting stories and even failed a polygraph test. Nor did the jury know that in exchange for her testimony, Frances Smith was allegedly given complete immunity from all charges, and that even her “unrelated” felony charges were dropped shortly after Lambrix was convicted.

No defense was presented, and in what can only be described as a bizarre set of circumstances, Lambrix’s own trial lawyer compelled that trial judge to advise Lambrix that if he insisted on testifying against counsel’s wishes, Lambrix would be striped of his legal counsel and forced to represent himself even though Lambrix only had a 9th grade formal education and no training in law. See, Lambrix v. Singletary, 72 F. 3d 1500 (11th Cir. 1996)

Thus, the jury never got to hear Lambrix’s claim of what really happened outside, even though star witness Frances Smith admitted that she did not see or hear anything that transpired outside. Lambrix was the only one who could have told the jury the jury what really happened – but he was involuntarily silenced. See, “A parody of justice,” St. Petersburg Times (Oct. 5, 2006)

In closing arguments, Lambrix trial counsel strenuously argued that substantial reasonable doubt existed that legally precluded a finding of guilty as the state had completely failed to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt as the law required. Trial counsel pointed out that the state’s entire theory of “premeditated” murder clearly conflicted with the evidence, as Smith admitted she never actually saw or heard anything that took place outside – and her claims of what Lambrix allegedly told her was contradicted by the evidence itself. The states own medical examiner confirmed that there was no actual evidence that Bryant had died of strangulation or drowning, as Smith had claimed, and in fact, there simply was no pond anywhere in that area.

Further the state’s medical examiner admitted that Moore was the only one who had suffered any physical injuries that would have resulted in the loss of blood. Since Smith testified that Moore went out first and when Lambrix returned alone before Bryant went out, Lambrix “looked normal: and had no blood on him, then Moore had to still be alive when Bryant went outside – whatever actually transpired that night had to happen spontaneously, without premeditated intent. See, “Trial Transcript: Closing Arguments.”

Additionally, all of the wounds to Moore’s head were to each side of his frontal temporal area, obviously administered in a consistent and continuous “swinging” motion, with Moore facing his assailant. The absence of any defense wounds strongly suggested that Moore had been the aggressor – not Lambrix.

Both Moore and Bryant each substantially outweighed Lambrix, so how could he have simultaneously killed both in two completely different ways? Although no clear cause of death for Bryant could be found, if Smith’s claim that Lambrix had “choked” Bryant was true, then we must ask whether a presumably healthy 19 year old woman significantly larger than Lambrix would have passively stood there without struggling or attempting to fight back? Smith admitted that Lambrix had no scratches or bruises as one would expect to find – but the autopsy on Moore revealed that he did have numerous scratches consistent with what would be inflicted by a woman trying to defend herself from an assault, implying that Moore was the one who had assaulted Bryant, not Lambrix. But the fingernail scrapings that might have conclusively identified Bryant’s true assailant conveniently disappeared.

With the state attorney again insisting that the collective circumstantial evidence clearly proved guilt of premeditated murder of both Aleisha Bryant and Clarence Edward Moore (aka Lawrence Lamberson) beyond any reasonable doubt, the prosecutor argued that the jury should convict Lambrix on both counts as charged in the indictment.

Following a “charge conference” between the court and counsel for both sides, the jury was instructed on the law applicable to the case, and then retired to the “jury room” to begin their deliberations in the early afternoon. Many hours passed and the long afternoon went into the night and then into the early morning hours without any verdict. The court recognized that it simply did not have the facilities to sequester the jury as the closest motel was about 30 miles away in the next county. After being repeatedly encouraged until they could reach a unanimous verdict, the jury finally announced that they could not agree on any verdict at all, and over Lambrix’s objection Judge Adam’s declared a “hung jury” and dismissed them. See, Lambrix v. Singletary, 72 F. 3d 1500 (11th Cir. 1996) (challenging deprivation of right to testify and improper discharge of original jury under double jeopardy grounds)

VII.) Convicting and Condemning Lambrix

After the first trial ended in a “hung jury” the prosecutor, Randall McGruther announced his plans to retry the case. The local weekly paper declared the Lambrix mistrial and capital murder case the biggest story of the year and continued to relentlessly in saturate the local community with the highly sensationalized prejudicial “facts” that were simply not true, but were intended to inflame the community into a lynch mob frenzy. Lambrix’s trial lawyers again filed a motion to have the case moved out of the small community, but that motion was summarily denied.

VI.) Taking the Case to a Jury Trial

After several days of jury selection, the actual trial began. In his opening arguments the prosecutor Randall McGruther conceded that there were no eyewitnesses, no physical or forensic evidence, and no confessions to support his theory if alleged premeditated murder – that the entire case was built up upon Frances Smith’s testimony, supported only by a web of circumstantial evidence that collectively “proved” premeditated murder.

Smith was called as the states star witness. She testified that by chance they met Moore and Bryant at the bar that night and “partied” together until the early morning hours. Lambrix then invited them back to the trailer. After an hour or so of “laughing, teasing, and playing around” Lambrix and Moore went outside only to have Lambrix return 20 alone minutes later. Lambrix then took Bryant out was gone for about 45 minutes before again returning alone – only this time Lambrix was “covered in blood” and told her “they’re dead.”

Smith then testified that while covered in blood, Lambrix grabbed her and threatened her – but incredibly did not get any blood on her or her clothing. Smith then claimed that Lambrix told her that he had hit the man in the back of the head, then choked Bryant before placing her face down in a pond to ensure that she died, even though medical evidence objectively showed that Moore was not hit in the back of the head, and there was no evidence that Bryant was choked or strangled – and no “pond” existed anywhere in that pasture area.

Smith implied that the motive was to steal Moore’s car – the very car that she alone was found in possession of. This otherwise unsupported theory of alleged premeditated murder was corroborated by state witness Deborah Hanzel, who at the time was the girlfriend of Smith’s cousin.

Hanzel testified that Lambrix also told her that he had killed Moore and Bryant so he could steal the car – but years later Hanzel recanted that testimony, claiming that Smith and the state had coerced her to provide false testimony and that Lambrix never told her he killed anyone. See, “Witness recants testimony in murder case,” Ft. Myers News-Press (Feb. 10, 2004)

Additional witnesses were called to establish particulars regarding the alleged crime scene and recovery if the two bodies. The local medical examiner, Dr. Robert Shultz, testified as to the cause of death of both Moore and Bryant. Dr. Shultz said that there was no question that Moore died of blunt force trauma resulting from numerous blows to the frontal temple area on both sides of his head, as if the blows were administered in a “swinging” fashion while Moore presumably faced his assailant. There were no blows to the back of the head (as Smith claimed), and no defense wounds – suggesting that Moore may have been the aggressor.

Robert “Bob” Daniels testified that he was the lead investigator assigned to the case, and was responsible for initiating the changes against Lambrix, then personally supervising the development of the wholly circumstantial case. Carla Mitar testified that she too was assigned by the state attorney’s office to assist in the investigation and development of the evidence. But the jury would not know that during the time Investigator Daniels, although married to Joan Daniels, was having an affair with Carla Mitar (who he later would marry). Many years later it would also be revealed that in addition to having an illicit affair with Carla Mitar, Daniels was also having a secret relationship “of a sexual nature” with star witness Frances Smith. See, “Witness admits affair with investigator,” Ft. Myers News-Press (Apr. 6, 2004).

Lambrix legal counsel were prohibited from revealing to the jury that star witness Frances Smith had told numerous conflicting stories and even failed a polygraph test. Nor did the jury know that in exchange for her testimony, Frances Smith was allegedly given complete immunity from all charges, and that even her “unrelated” felony charges were dropped shortly after Lambrix was convicted.

No defense was presented, and in what can only be described as a bizarre set of circumstances, Lambrix’s own trial lawyer compelled that trial judge to advise Lambrix that if he insisted on testifying against counsel’s wishes, Lambrix would be striped of his legal counsel and forced to represent himself even though Lambrix only had a 9th grade formal education and no training in law. See, Lambrix v. Singletary, 72 F. 3d 1500 (11th Cir. 1996)

Thus, the jury never got to hear Lambrix’s claim of what really happened outside, even though star witness Frances Smith admitted that she did not see or hear anything that transpired outside. Lambrix was the only one who could have told the jury the jury what really happened – but he was involuntarily silenced. See, “A parody of justice,” St. Petersburg Times (Oct. 5, 2006)

In closing arguments, Lambrix trial counsel strenuously argued that substantial reasonable doubt existed that legally precluded a finding of guilty as the state had completely failed to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt as the law required. Trial counsel pointed out that the state’s entire theory of “premeditated” murder clearly conflicted with the evidence, as Smith admitted she never actually saw or heard anything that took place outside – and her claims of what Lambrix allegedly told her was contradicted by the evidence itself. The states own medical examiner confirmed that there was no actual evidence that Bryant had died of strangulation or drowning, as Smith had claimed, and in fact, there simply was no pond anywhere in that area.

Further the state’s medical examiner admitted that Moore was the only one who had suffered any physical injuries that would have resulted in the loss of blood. Since Smith testified that Moore went out first and when Lambrix returned alone before Bryant went out, Lambrix “looked normal: and had no blood on him, then Moore had to still be alive when Bryant went outside – whatever actually transpired that night had to happen spontaneously, without premeditated intent. See, “Trial Transcript: Closing Arguments.”

Additionally, all of the wounds to Moore’s head were to each side of his frontal temporal area, obviously administered in a consistent and continuous “swinging” motion, with Moore facing his assailant. The absence of any defense wounds strongly suggested that Moore had been the aggressor – not Lambrix.

Both Moore and Bryant each substantially outweighed Lambrix, so how could he have simultaneously killed both in two completely different ways? Although no clear cause of death for Bryant could be found, if Smith’s claim that Lambrix had “choked” Bryant was true, then we must ask whether a presumably healthy 19 year old woman significantly larger than Lambrix would have passively stood there without struggling or attempting to fight back? Smith admitted that Lambrix had no scratches or bruises as one would expect to find – but the autopsy on Moore revealed that he did have numerous scratches consistent with what would be inflicted by a woman trying to defend herself from an assault, implying that Moore was the one who had assaulted Bryant, not Lambrix. But the fingernail scrapings that might have conclusively identified Bryant’s true assailant conveniently disappeared.

With the state attorney again insisting that the collective circumstantial evidence clearly proved guilt of premeditated murder of both Aleisha Bryant and Clarence Edward Moore (aka Lawrence Lamberson) beyond any reasonable doubt, the prosecutor argued that the jury should convict Lambrix on both counts as charged in the indictment.

Following a “charge conference” between the court and counsel for both sides, the jury was instructed on the law applicable to the case, and then retired to the “jury room” to begin their deliberations in the early afternoon. Many hours passed and the long afternoon went into the night and then into the early morning hours without any verdict. The court recognized that it simply did not have the facilities to sequester the jury as the closest motel was about 30 miles away in the next county. After being repeatedly encouraged until they could reach a unanimous verdict, the jury finally announced that they could not agree on any verdict at all, and over Lambrix’s objection Judge Adam’s declared a “hung jury” and dismissed them. See, Lambrix v. Singletary, 72 F. 3d 1500 (11th Cir. 1996) (challenging deprivation of right to testify and improper discharge of original jury under double jeopardy grounds)

VII.) Convicting and Condemning Lambrix

After the first trial ended in a “hung jury” the prosecutor, Randall McGruther announced his plans to retry the case. The local weekly paper declared the Lambrix mistrial and capital murder case the biggest story of the year and continued to relentlessly in saturate the local community with the highly sensationalized prejudicial “facts” that were simply not true, but were intended to inflame the community into a lynch mob frenzy. Lambrix’s trial lawyers again filed a motion to have the case moved out of the small community, but that motion was summarily denied.

- Glades County Courthouse -

In February 1984, the retrial was scheduled to begin once again; Lambrix was advised to plead guilty to the lesser charges of second degree murder, but refused. Had he agreed to accept this “plea bargain,” Lambrix would have faced a sentence of only 17 to 22 years. Under Florida’s “gain time” system Lambrix would have served no more than 12 to 15 years in prison. But Lambrix steadfastly maintained his innocence of any “murder” and insisted on his right to a jury trial.

The local political pressure to win a conviction could not have been greater, and the prosecutor Randall McGruther knew that. On the first day of the retrial, Lambrix’s lawyers were blindsided by the previously unannounced and inexplicit substitution of the original trial judge (Adams) by Judge Richard Stanley. This was not a good thing and illustrated the state’s intent to win a conviction by any means necessary as Judge Stanley’s reputation was well known. Prior to becoming a circuit court judge in adjacent Charlotte County, Judge Stanley was a career prosecutor in the area — describing himself as the “meanest son of a bitch” and a zealous advocate of the death penalty.

Judge Stanley only ran for circuit court judge after his colleague and long time friend in the local states attorney’s office was murdered, gunned down by an unknown assailant – the case was never solved. Vowing to avenge his colleague, Judge Stanley promised to send the killers to death row. His personal campaign against capital defendants became known years later when the Florida Supreme Court vacated another death sentence imposed by Judge Stanley, recognizing that his obvious bias deprived the capital defendant of a fair trial before an impartial tribunal. See, Porter v. State, 723 So. 2d 191 (Fla. 1998).

Judge Stanley’s agenda became clear from the beginning when he used his influence as the judge to manipulate the selection of a jury that included four jurors directly related to the local Glades County Sheriff’s Office, including Juror Winburn – who was the step father of local Sheriff’s deputy Ralph Alan Green, who at the time of Lambrix’s trial was under an active FBI investigation for brutally assaulting Lambrix in the county jail only two months earlier. Review of the jury selection process also reveals that the jury foreman (Snyder) admitted that before he even heard any evidence, he already believed Lambrix was guilty. (See, Actual Innocence Appeal, “Claim I”). Clearly the state had no intention of giving Lambrix a “fair trial.”

After selecting the new jury, the state presented its case for the second time, which was basically identical to their prior presentation. Again Lambrix’s trial counsel were prohibited from cross-examining the star witness Frances Smith on the numerous conflicting stories that she gave to law enforcement prior to coming up with the one that the state latched on to, to argue their theory of capital murder. Nor was the jury allowed to know that Smith had failed a polygraph test. Or that the male victim (Moore) was actually a career criminal with a history of violently assaulting women and that the objective evidence actually supported a conclusion that Moore attacked and killed the female victim (Bryant), not Lambrix.

Once again, Lambrix was prohibited from personally testifying and no defense was presented beyond an argument that the evidence did not prove capital murder beyond the legally required “reasonable doubt” – that the evidence the state presented clearly contradicted the prosecutors theory as Moore had to still be alive when Bryant went outside and whatever might have happened that resulted in their deaths could not have happened as the prosecutor claimed.

This time the jury deliberated barely an hour before coming back with a verdict of guilty on both counts of first degree murder, as charged in the indictment. Following a brief “sentencing phase,” the same jury recommended by majority vote that Lambrix be sentenced to death.

On March 22, 1984 Lambrix was formally sentenced to death. In imposing this sentence, Judge Stanley refused to recognize any “mitigating” circumstances even though the undisputed evidence established numerous statutory and non-statutory “mitigators” including that Lambrix was honorably discharged for the Army following a disabling duty related accident, was a former Boy Scout, and Catholic alter boy, as well as the father of three young children with no significant criminal history. Years later when Lambrix’s case was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, the full court recognized that Lambrix was unconstitutionally sentenced to death – but by a marginal vote of 5 to 4, the conservative majority ruled that because Lambrix’s appointed legal counsel failed to timely challenge this illegal sentence, Lambrix could not be granted relief. See, Lambrix v. Singletary, 520 U.S. 518 (1997).

In February 1984, the retrial was scheduled to begin once again; Lambrix was advised to plead guilty to the lesser charges of second degree murder, but refused. Had he agreed to accept this “plea bargain,” Lambrix would have faced a sentence of only 17 to 22 years. Under Florida’s “gain time” system Lambrix would have served no more than 12 to 15 years in prison. But Lambrix steadfastly maintained his innocence of any “murder” and insisted on his right to a jury trial.

The local political pressure to win a conviction could not have been greater, and the prosecutor Randall McGruther knew that. On the first day of the retrial, Lambrix’s lawyers were blindsided by the previously unannounced and inexplicit substitution of the original trial judge (Adams) by Judge Richard Stanley. This was not a good thing and illustrated the state’s intent to win a conviction by any means necessary as Judge Stanley’s reputation was well known. Prior to becoming a circuit court judge in adjacent Charlotte County, Judge Stanley was a career prosecutor in the area — describing himself as the “meanest son of a bitch” and a zealous advocate of the death penalty.

Judge Stanley only ran for circuit court judge after his colleague and long time friend in the local states attorney’s office was murdered, gunned down by an unknown assailant – the case was never solved. Vowing to avenge his colleague, Judge Stanley promised to send the killers to death row. His personal campaign against capital defendants became known years later when the Florida Supreme Court vacated another death sentence imposed by Judge Stanley, recognizing that his obvious bias deprived the capital defendant of a fair trial before an impartial tribunal. See, Porter v. State, 723 So. 2d 191 (Fla. 1998).

Judge Stanley’s agenda became clear from the beginning when he used his influence as the judge to manipulate the selection of a jury that included four jurors directly related to the local Glades County Sheriff’s Office, including Juror Winburn – who was the step father of local Sheriff’s deputy Ralph Alan Green, who at the time of Lambrix’s trial was under an active FBI investigation for brutally assaulting Lambrix in the county jail only two months earlier. Review of the jury selection process also reveals that the jury foreman (Snyder) admitted that before he even heard any evidence, he already believed Lambrix was guilty. (See, Actual Innocence Appeal, “Claim I”). Clearly the state had no intention of giving Lambrix a “fair trial.”

After selecting the new jury, the state presented its case for the second time, which was basically identical to their prior presentation. Again Lambrix’s trial counsel were prohibited from cross-examining the star witness Frances Smith on the numerous conflicting stories that she gave to law enforcement prior to coming up with the one that the state latched on to, to argue their theory of capital murder. Nor was the jury allowed to know that Smith had failed a polygraph test. Or that the male victim (Moore) was actually a career criminal with a history of violently assaulting women and that the objective evidence actually supported a conclusion that Moore attacked and killed the female victim (Bryant), not Lambrix.

Once again, Lambrix was prohibited from personally testifying and no defense was presented beyond an argument that the evidence did not prove capital murder beyond the legally required “reasonable doubt” – that the evidence the state presented clearly contradicted the prosecutors theory as Moore had to still be alive when Bryant went outside and whatever might have happened that resulted in their deaths could not have happened as the prosecutor claimed.

This time the jury deliberated barely an hour before coming back with a verdict of guilty on both counts of first degree murder, as charged in the indictment. Following a brief “sentencing phase,” the same jury recommended by majority vote that Lambrix be sentenced to death.

On March 22, 1984 Lambrix was formally sentenced to death. In imposing this sentence, Judge Stanley refused to recognize any “mitigating” circumstances even though the undisputed evidence established numerous statutory and non-statutory “mitigators” including that Lambrix was honorably discharged for the Army following a disabling duty related accident, was a former Boy Scout, and Catholic alter boy, as well as the father of three young children with no significant criminal history. Years later when Lambrix’s case was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, the full court recognized that Lambrix was unconstitutionally sentenced to death – but by a marginal vote of 5 to 4, the conservative majority ruled that because Lambrix’s appointed legal counsel failed to timely challenge this illegal sentence, Lambrix could not be granted relief. See, Lambrix v. Singletary, 520 U.S. 518 (1997).

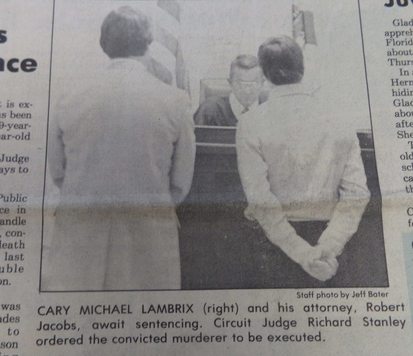

- March 22, 1984. Michael Lambrix sentenced to death by Judge Richard Stanley -

VIII.) Motive to Wrongfully Convict

Our criminal justice system is designed to incorporate a series of safeguards to protect against prosecuting and convicting the innocent. The first wall of protection is the separation of the investigating and prosecuting agencies. Almost without exception, a criminal case is investigated and evidence developed by a local law enforcement agency such as the police or sheriff’s department. Only then is that evidence turned over to the state (or district) attorney for prosecution. This separation of investigatory and prosecution agencies serves the purpose of promoting objectivity.

A state attorney is ethically responsible for protecting the rights of all citizens, including the accused. The prosecutor does not represent the victim, but rather represents the state in the pursuit of justice. A state attorney is required to independently examine the evidence to objectively determine whether the evidence and witnesses are credible and a prosecution can be pursued “in good faith.” It’s not a prosecutor’s job to manipulate or suppress evidence to win a conviction by any means necessary.

One of the significant factors that made the Lambrix case unique is that these traditional safeguards of separation between investigative and prosecution teams did not exist. Rather, from the very onset of this case the local state attorney, Randall Mc Gruther, took control of the case and the entire investigation and development if the wholly circumstantial evidence was personally controlled by his own lead investigator, Miles Robert (Bob) Daniels. Why is it that Mc Gruther and Daniels took control of this capital case rather than allow the local sheriff’s office to conduct the investigation?

As stated earlier, this particular alleged capital crime took place in one of the smallest counties of the traditional “Deep South.” At the time the prosecutor (Mc Gruther) was young and ambitious – and anxious to make a name for himself. Even before Lambrix was even arrested, Mc Gruther was already personally feeding the local weekly newspaper his own dramatically sensationalized theory of cold-blooded murder, unethically manipulating the small community into a lynch mob frenzy. See, Trial Transcripts – Jury Selection. (Jurors admitted to being exposed to an insaturation of local sensationalism).

But the whole story as to the real motivation for deliberately fabricating this sensationalized theory of cold-blooded murder was not exposed until many years later, when it was finally revealed why Mc Gruther and Daniels collaborated together to wrongfully convict and condemn Lambrix… and why they deliberately concealed this information for so long.

As the court records reflect, in 1998 former state witness Deborah Hanzel came forward and admitted that she provided false testimony against Lambrix at trial – that Lambrix never did tell her he killed anyone. (See, Actual Innocence Appeal,” claim II). Subsequently, Hanzel provided an affidavit and sworn testimony detailing how before Lambrix was even indicted, the star witness (Frances Smith) and the states investigator “Bob” Daniels coerced her to provide that crucial false testimony that corroborated Frances Smith’s testimony – that Lambrix admitted intentionally killing both Moore and Bryant.

Hanzel also testified under oath that they knew that Lambrix actually only said he acted in involuntarily self-defense when “the guy (Moore) went nuts,” but that they deliberately kept this from the jury. (See, Affidavit of Deborah Hanzel). At a court hearing in February, 2004 Hanzel’s claims were substantiated by telephone records.

In an apparent attempt to dispute Hanzel’s claim of an actual collaboration and conspiracy to wrongfully convict Lambrix, the state brought Frances Smith in to again testify. But just before this court hearing Lambrix’s counsel received additional information from Smith’s recently divorced ex-husband Douglas who claimed that Smith had often bragged about how she was having a sexual affair with the state attorney’s investigator “Bob” Daniels, at the time Lambrix was prosecuted.

Why is this information so important? Because suddenly the motivation and means of wrongfully convicting Lambrix became clear. Investigator “Bob” Daniels was instrumental in bringing the case against Lambrix — Daniels personally swore out the affidavit that led to formal charges of capital murder being brought against Lambrix, then subsequently personally supervised the entire investigation and development of the wholly circumstantial evidence used to convict and condemn Lambrix.

In April 2004 Frances Smith once again took the witness stand and was placed under sworn oath, completely unaware that her own ex-husband had informed Lambrix’s counsel of her secret illicit affair with Investigator Daniels. Confronted with this information, at first Smith perjurously denied the allegation – but then over the state attorney’s relentless objections, Smith hung her head and in barely a whisper, she reluctantly admitted it was true. (See, “Actual Innocence Appeal,” claim IV) (See also, Ft. Myers News-Press, April 6th, 2004 “Witness admits to affair with investigator.”)

Additional evidence was developed that substantiated an actual conspiracy and collaboration between Frances Smith and the state attorney’s office to, by deliberate intent and design, wrongfully convict and condemn Lambrix. (Please see, “Actual Innocence Appeal,” claim III). Collectively the wealth of this evidence leaves no doubt that star witness Frances Smith and State Attorney Investigator “Bob” Daniels worked together to manipulate and fabricate evidence, and coerce witnesses to provide false testimony – and that state attorney Randall Mc Gruther knew that Smith and Daniels were working together to manipulate and fabricate crucial evidence.

It must also be recognized that state attorney Randall Mc Gruther is a career prosecutor with a history of alleged misconduct that includes attempting to coerce false testimony from witnesses, as well as sending at least one other innocent man to death row in another wholly circumstantial capital case. (Please read, “The Anatomy if a Corrupt Prosecutor.”)

Would the jury that convicted and condemned Lambrix reach the same verdict if they had known about the illicit relationship between Investigator Daniels and Frances Smith? Equally so, what if the jury had also known (as the state now concedes) that the star witness (Smith) had actually told numerous conflicting stories and even failed a polygraph test? Or that the only witness that actually corroborated Smith’s testimony now admits that she was coerced to provide false testimony and, in fact, Lambrix never told her he killed anyone? And that the male deceased (Moore/Lamberson) actually was a career criminal with a history of violently assaulting woman, and that the state deliberately suppressed evidence that Lambrix acted in involuntary self-defense?

These now undisputed facts were never known to the jury that convicted and condemned Lambrix. But now you have the opportunity to read the complete trial transcript; to fully consider all the evidence the jury heard as well as the evidence now available that the jury never heard… You be the jury.

IX.) Lambrix’s Claim of Self-Defense

As the Supreme Court has long recognized, a criminal defendant’s right to personally testify in his own defense is one of the most basic and fundamental constitutional rights that any criminal defendant has. This is especially true when a person is charged with capital murder based solely upon the testimony of a single witness in a wholly circumstantial case with no eyewitnesses, no physical or forensic evidence, and no confessions.

In fact it would be fair to say that if, in such a case, the states witness took the stand and claimed that although she didn’t see anything, but that you had told her you committed murder with intent to kill, if you did not take the witness stand yourself to deny those allegations, the average juror might take that silence itself as an admission of guilt. When it comes down to it, we would expect a defendant to want to deny such allegations if they were not already true.

But what if the jury didn’t know that the defendant did want to testify, only to have his lawyers say, “No, we don’t want you to?” This is what happened in the Lambrix case. There is no question that Lambrix specifically informed his lawyers that he did want to testify, and when Lambrix kept insisting that he be allowed to testify, Lambrix’s own lawyers went to the trial judge and had the judge instruct Lambrix that if he continued to insist on testifying over counsel’s objections, the judge would allow Lambrix’s lawyers to abruptly withdraw, and Lambrix would be involuntarily forced to represent himself. See, Lambrix v. Singletary, 72 F. 3d 1500 (11th Cir. 1996).

As fully stated in appellate briefs filed in this case many years ago, Lambrix has consistently raised his claim of the deprivation of his fundamental right to testify at every stage of post-conviction appellate proceedings, (See, “Post Conviction Appeal”), only to be repeatedly thwarted by the states argument that review was “procedurally barred” because Lambrix’s lawyers failed to properly raise the claim. Incredibly, the state courts have refused to address the merits of Lambrix’s claim of self-defense because the technical presentation of that claim was imperfect. See, Lambrix v. State, 698 So. 2d 247 (Fla. 1996); (See also, “Parody of Justice,” M. Dyckman, St. Petersburg Times, August 31, 1997).

Perhaps even more troubling is the state attorney’s own unethical misrepresentations when responding to Lambrix’s pled claim of self-defense. Unable to dispute the merits of Lambrix’s claim, the state attorneys (Randall Mc Gruther, Cynthia A, Ross, and Carol M. Dittmar) have attempted to argue that this claim of self-defense was somehow recently fabricated, even though court records show that Lambrix has raised this claim consistently for over 20 years, and Lambrix has never advanced any other story. See, “Florida Bar Complaints” (Pending against state attorneys Cynthia A, Ross and Carol M. Dittmar).

Only when this “new evidence” of the state attorney’s conspiracy and collaboration to wrongfully convict and condemn Lambrix was revealed (See, “Actual Innocence Appeal,” claim III) was Lambrix finally provided an opportunity to take the stand and testify under oath at an evidentiary hearing in April, 2004. At that time, Lambrix detailed his claim of involuntary self-defense and how the star witness, Frances Smith, knew Lambrix had acted in self-defense all along. As the court records reflect, when the state then had the opportunity to cross-examine and discredit Lambrix, the state did not and could not produce any evidence to dispute Lambrix’s claims. (See, “Excerpt of Testimony: Michael Lambrix”)

Certainly, it would stand to reason that if there was any evidence to discredit Lambrix’s claims, the state would have been eager to produce it. The fact is that the evidence supports Lambrix’s claims – Moore was still alive when Lambrix went back outside with Bryant, so the State’s theory that Lambrix “lured” Moore out first and killed him, then returned to take Bryant and kill her simply is not consistent with the evidence. See, “Trial Transcript: Closing Arguments”) How could Lambrix have killed two people at the same time, both significantly larger than he was, in two entirely different ways? It makes no sense.

Further, Lambrix’s claim of what actually happened that night is actually consistent with star witness Smith’s account – up until the time Lambrix went outside with Moore and Bryant. Smith concedes that she did not see or hear anything that took place outside, and that when she last saw Lambrix with Moore and Bryant, they were all “laughing, teasing, and playing around” with no suggestion of animosity. As the trial transcript reflects, the entire theory of “premeditated” murder was based upon Smith’s claim that Lambrix subsequently told her that he killed them with the intent to steal Moore’s car – the car that Smith alone had possession of.

As reflected in court records (See, “Actual Innocence Appeal), the evidence now shows that Frances Smith conspired and collaborated with her “lover,” the state attorney’s own investigator “Bob” Daniels, to maliciously fabricate this claim and coerce false testimony to support it. Lambrix was the only person who could have told the jury that Smith was lying. But Lambrix was silenced. As the record reflects, had Lambrix been allowed to testify, this is what he would have told the jury; (See, “Excerpt of Testimony: Michael Lambrix”).

Lambrix readily admits to meeting Moore and Bryant at the bar that night and after many hours of heavy drinking and dancing together, Lambrix invited them back to his house for a late night dinner. After arriving at the trailer, Lambrix, Moore, and Bryant sat in the living room drinking and “playing around,” while Smith remained in the adjacent kitchen cooking dinner.

After awhile, Lambrix and Moore decided to go outside to Moore’s car to get some music tapes. Both now unquestionably intoxicated after many hours of drinking, in their drunken stupor they impulsively concocted a plan to play a practical joke on the two women. As Moore hid behind a nearby cattle feed trough Lambrix went back inside the trailer and told Smith and Bryant that they (Lambrix and Moore) had something outside that they wanted to show them. But Smith was still cooking dinner and she stayed inside as only Bryant accompanied Lambrix back outside.